Panama, Costa Rica (2004)

The Big Ditch

Our cruise took us south along the beautiful and largely undeveloped Pacific coast of Costa Rica and Panama and was climaxed with a passage through the Panama Canal.

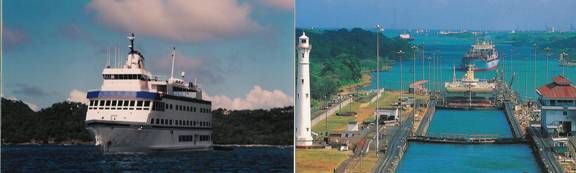

M/S Pacific Explorer Gatun Lock – Panama Canal

Costa Rica. It’s hard not to be impressed with Costa Rica. A small country with fewer than four million people, Costa Rica has a stable, democratically-elected government, more teachers than police and no military. It is a richly bio-diverse country claiming more species of flora and fauna per square mile than any other country in the world. The people of Costa Rica have a strong commitment to the environment and have set apart over 25% of the country for national parks and nature preserves. As a result, Costa Rica has become a favorite destination for travelers interested in eco-tourism.

It is also a beautiful and geographically diverse country. Our bus ride from the capital city of San Jose to the Pacific coast took us through the shimmering green-leaves of the coffee plantations of the central valley, over the rugged coastal mountains and down to the jungle-lined beaches of the coast all in a matter of a few hours. We boarded our ship in Jaco and spent the next nine days cruising along the Pacific shores and coastal islands of Costa Rica and Panama as we headed toward the Panama Canal.

Our ship, the 175 foot Pacific Explorer, carried just 96 passengers plus a crew of 30. It was comfortably appointed with fifty air-conditioned cabins, a dining room, two lounges and a large sun desk. The ship’s small size and shallow draft allowed us to anchor in close to isolated beaches and small villages that would have been inaccessible to larger ships. The crew included five naturalists who gave nature talks on board and who led the passengers on bird hikes and nature walks on shore. Their knowledge of the local wildlife was limitless and the stories were fascinating on everything from leaf-cutter ants to sea turtles to three-toed sloth. For example, did you know that a leaf-cutter ant colony can process 100 pounds of leaves per day . . . that green sea turtles circumnavigate the world’s oceans but always return to within a few miles of their birthplace to lay their eggs . . or that sloth only come down from their perch high in the trees twice a month to defecate? Fascinating stuff.

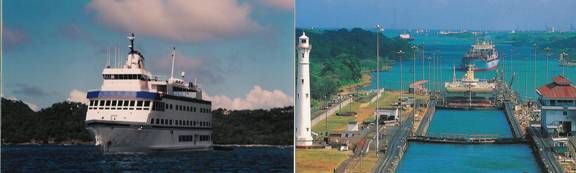

White Face Capuchin Monkey Iguana

Our first two ports of call were the Manuel Antonio and the Corcovado National Parks south along the Costa Rican coastline. These two parks boast wildlife in astonishing abundance. Almost 10% of the mammal species in the Western Hemisphere live in these parks. Hiking through the parks in small groups with our naturalists and we saw capuchin, howler and spider monkeys, sloth, agouti and numerous iguana. Our guides were primarily bird lovers with uncanny abilities to spot birds moving and flitting about in the dense foliage of the jungle. At the conclusion of our beach picnic at Corcovado, we were treated to a flight of scarlet macaws flying low overhead flashing their brilliant colors against the blue sky immediately followed by a troupe of white-faced capuchin monkeys, who descended, as if on cue, to our campsite to provide after-lunch entertainment.

Panama. Our coastal adventure continued into Panamanian waters with twice daily Zodiac excursions ashore for bird watching and nature hikes, visits to indigenous native villages or just relaxing on isolated, palm lined sand beaches for swimming, snorkeling and sunning. As we progressed along the coast, we were surprised at how isolated and totally undeveloped the Pacific coastline of Costa Rica and Panama is. We saw few other ships or people for days. Our nature studies weren’t limited exclusively to shore excursions. From the bow of the ship, we spotted dolphins, sea snakes and sea turtles as we plowed our way along the coast.

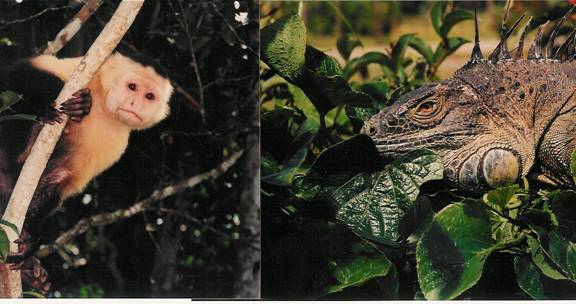

The native villages were fascinating. The Darien peninsula was the location of an Embara Indian village, where a community of three hundred Indians lives a simple and isolated life of subsistence farming and fishing. The people live in elevated, bamboo-roofed houses without electricity or running water, cook with wood and light their homes with oil extracted from coconuts. They received us warmly, if shyly, performed some traditional dances and offered handicrafts for sale. They even took on the ship’s crew in a hotly contested game of soccer in which the crew had to struggle to tie the game in the final minutes against the bare-footed but highly skilled natives. Inevitably, we were invited to join the locals in their dances and, reminiscent of our trip last year up the Amazon, I found myself in the jungle once again dancing with bare breasted women. I’m learning to enjoy it.

Embara Girl with her Brother Valerie Negotiating with Embara Women Kuna Girl with her Parrot

The Kuna Indians of the San Blas islands were even more interesting living on small, isolated and remote islands in the Caribbean and relying on fishing as their primary source of food. Believed to be descendents of the ancient Caribs, the Kuna Indians still live in much the same manner as their ancestors. The San Blas people have managed to retain their tribal identity and to lead a simple life, free from the complexities of modern society. Granted political independence by the Panamanian government several generations ago, these diminutive people are distinguished by their short stature, their gold nose rings, the beaded arm bands and leggings of the women and their colorful “mola”, a reverse appliqué cloth blouse decoration which has become an important tourist handicraft.

Although not truly indigenous, the Afro-Caribbean people that inhabit the sleepy Caribbean port town of Portobelo are equally colorful. The people are mostly descendents of the Barbados islanders, who came to Panama a hundred years ago to work on the Panama Canal. This historic town, named “Beautiful Port” by Columbus when he landed there on his fourth and final voyage to the New World in 1502, served as a depot for the gold, silver and precious stones that were pillaged from the Incas and Aztecs along the Pacific Coast by the Spanish conquistadores before shipment back to Spain. The riches soon attracted the Henry Morgans, Frances Drakes and the other pirates of the Caribbean, who raided the town and plundered the gold treasures in the 16th and 17th centuries. The massive stone fortresses with their rows of cannon pointed out to the sea have long since fallen into ruin, a sad symbol of what was once the most important town in the New World. It was here that Valerie was chosen by one of the young locals to join him in a wild dance known as the Congos, in which dancers dress in mock military uniforms and lampoon Spanish colonial officials. It didn't take her long to master all the moves.

Panama Canal The transit through the Panama Canal was the highlight of the trip for both of us. Having heard and read about the Canal for our entire lives, it was a dream come true to see this wonder of the modern world . . . a monumental engineering achievement of the 20th Century, which pushed the advancement of technology and provided a source of national pride for our grandparents almost one hundred years ago . . . much as the moon landing did for our generation.

The history of the canal . . . the failed first attempt by the French, the protracted debates over the best route, Teddy Roosevelt’s gunboat diplomacy, Panamanian independence, the heroic battles to eliminate yellow fever and malaria and the stories of the great men, who oversaw the construction are all well documented in David McCullough’s excellent book “The Path Between the Seas. 10 years under construction. 350 million dollars in cost. 260 million cubic yards of earth moved. 45,000 workers employed at the peak of construction. 5,600 deaths from disease and accidents. . . or 25,000 deaths, if the initial construction by the French is taken into account. These are only a few of the statistics which give some dimension to the magnitude of the undertaking.

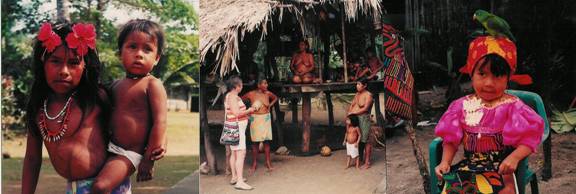

The final engineering plan was simple in concept. Dam the Chagres River to form a massive lake at the center of the isthmus. Blast through the Culebra Cut separating the lake from the Pacific and build a series of three locks at each end to lift the ships the 85 feet from sea level to the lake level. Under this concept, less than half of the fifty mile canal is through a narrow channel. The rest is across Gatun Lake, the largest man-made lake of its day.

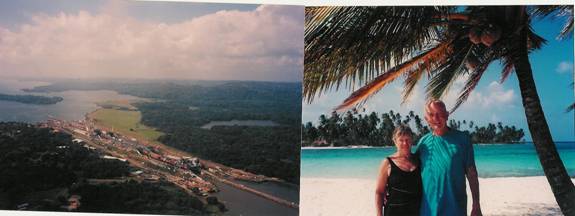

Gatun Locks – Panama Canal from Helicopter San Blas Island Paradise

Our transit time through the canal was seven hours. The tariff was $13,000 based on our size. Unfortunately, we were assigned to cross the canal at night, the daytime hours generally being reserved for the large passenger and container cargo ships. Although the locks are well illuminated at night, we would have preferred a daytime crossing. Nevertheless, we all stayed up to watch the opening and closing of the massive lock gates, the raising and lowering of the water level and the movement of the ship into and out of the locks with the electric locomotives (known as mules) which help center and move the ship as it passes through each lock. Amazingly most of the canal remains exactly the same as it was when it was completed in 1914 . . . a tribute to those who carried out this vast, unprecedented feat of engineering almost one hundred years ago.

We had several more daytime opportunities to see the Canal in our final days in the country. . . from an observation tower high above the rainforest near our hotel, from a little outboard boat, which took us up the canal alongside some of the passing ships and, most exciting of all, a flight on a small, two-seat, open cockpit helicopter, which flew the entire length of the canal from Colon on the Atlantic to Panama City on the Pacific. Swooping low over the rivers and soaring high over the rain forest, it was a flight worthy of the full Cinemax treatment Apart from the thrill of having only a seat belt between me and the jungle below, the experience helped to finally fix the geography of the entire canal in my mind. . . . although it may always be difficult to accept that the canal actually runs north and south and not east and west.

Our final three days were spent at the Gamboa Rainforest Lodge, a luxury resort located on the Chagres River, a half mile upstream of where the river flows into the canal. It was from here that we took our boat ride and helicopter flight on which we got our final views of the canal. It was a nice way to bring our Central American adventure to a close.

.