Antarctica 2000

Expedition to the Bottom of the World

When we told our friends that we were planning a trip to Antarctica, half of them said "Wow!"; the other half asked "Why ?!?" It was hard to come up with a good answer to that question at the time because the breathtaking beauty of Antarctica really cannot be imagined beforehand. Now that we've been there, I think we can offer an answer :

Antarctica has the most spectacular scenery of any place on earth. Antarctica has its own unique wildlife in overwhelming numbers. And, an expedition to Antarctica is a true adventure, where weather and ice . . not clocks and calendars . . determine the itinerary. There’s a fourth reason, too . . . Minnesotans like to go South in the winter.

It is a long way from White Bear Lake to Antarctica . . . a flight to New York connecting with a flight to Santiago (Chile), a charter flight to the southern tip of Argentina and finally a two day trip by sea across the Southern Ocean to arrive on the Seventh Continent. The total trip (including our side trip to Easter Island on the way down) covered over 23,000 miles . . . 20,000 by air and 3,000 by sea . . . which is almost equivalent to circling the globe. It was worth the ride.

Geography.

Antarctica is the fifth largest continent . . . as large as the United States and Europe combined. And that’s just in the Summer. In the Austral (Southern) winter it doubles in size as the surrounding seas freeze extending the ice out to two hundred miles from the actual continent. Over 98% of the continent is covered with ice which averages two miles in depth and in places exceeds three miles. 95% of all the ice on earth is found in the Antarctic ice cap. In fact, it constitutes 75% of all the earth’s fresh water.

We were surprised to learn that the Antarctic continent is the highest of all the continents with the central plateau regions averaging 9,300 feet . . of which almost 9,000 feet is ice. The highest mountain, the Vincent Massif, is over 16,000 feet. It is also the driest continent with the central plateau receiving less than two inches of precipitation each year.

Unlike the Arctic region, which is an ocean surrounded by land, the Antarctic is land surrounded by water. From Cape Horn, a sailor could sail around the earth at that latitude and never sight land. It is for this reason that the winds, uninterrupted by any land mass, can achieve high velocities and whip up some of the most furious seas in the world . . the Roaring Fifties . . . which are channeled at the Horn into the dreaded and infamous Drake Passage. These inhospitable seas, too, may in part explain why it was less than two hundred years ago than man first set foot of this continent at the bottom of the world.

History

The Ancient Greeks sensed that there was a continent at the south pole which "kept the earth in balance" and first showed it on a map in 150 A.D. as Terra Australis Incognita. But it wasn’t until 1821 that sealers first landed on the continent and not until 1898 that anyone spent the winter there. This was followed by the heroic age of polar expeditions which included Scott and Amundson’s famous race to the pole, Shackleton’s ill fated attempt to cross the continent (more later) and, most recently, our Minnesota’s own Will Steger first successful dogsled crossing of the continent in 1992..

The Antarctic Treaty was signed in 1961 and states that no one nation shall ever own Antarctica . . . nor remove of any animal, mineral or vegetable riches, noting that Antarctica’s true wealth lies in it’s unique status as a free, open and non- militarized land of international cooperation, scientific research and unsullied natural beauty. It is a treaty without teeth and dependent solely on the good will of the signatories (43 nations) but seems to date to be working out well.

The first tourists began arriving in the 1960’s in small numbers and that number has been growing annually. Today, there are about 10,000 tourists visiting Antarctica annually almost all of them in small cruise ships such as ours.

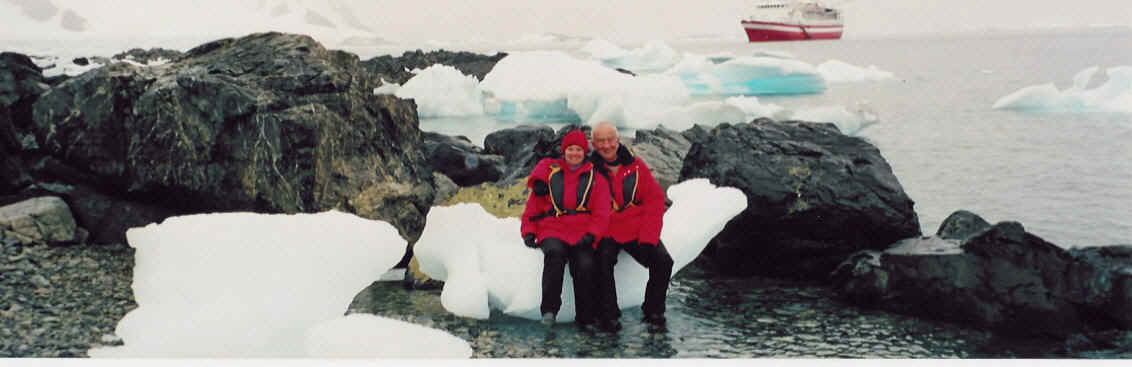

The Little Red Ship.

After a short bus tour of the Tierra del Fuego National Park, we boarded our ship in Ushuaia, Argentina, which bills itself as the southern-most city in the world, and set sail for Antarctica. Our "little red ship", the M.S. Explorer is a 238 foot long, 2,400 ton cruise ship built in 1969 with a reinforced hull constructed specifically for Antarctic travel. It carried a crew of 65 plus six naturists, who brought with them a wide variety of academic and scientific experience on everything from glaciology to Antarctic bird life. They gave four or five lectures a day while the ship was underway, led the shore excursions and joined us at meals and in the lounge for informal conversation and added greatly to our entire experience. The Captain was, perhaps, the most experienced skipper in the Antarctica, veteran of over thirteen seasons in the southern waters and proud of his ability (and his personal charts) which allowed him to get us into locations where other ships could not.

The eighty passengers were largely our age . . . retired, well-traveled and congenial. Eighteen were Brits; the rest from the U.S. All meals were open seating so by the end of the cruise we had a chance to meet and get to know a little about just about everyone.

Our first two days underway involved the 800 mile traverse across the notorious Drake Passage . . . considered by some as a initiation rite for travelers to the Southern Continent . .. with it’s threat of 50 foot waves and gale-force winds. The barf bags placed by the crew in the cabins and every three feet along the interior corridors coupled with the bowl of Dramamine in the lounge presented an ominous sign of what was to come. But the sea gods smiled and we had nothing but glassy seas all the way across the Drake in what the Captain billed as his smoothest crossing in the last several years. As an old sea dog, I have to confess to a little perverse disappointment at not experiencing the Drake in all it’s fury . . . but that thought passed quickly.

|

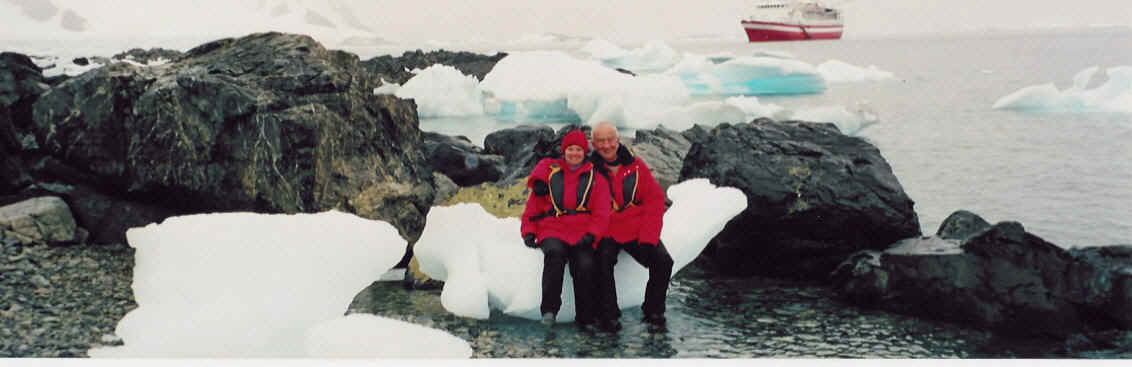

The Little Red Ship In Our Zodiacs Among the Icebergs

Antarctica

We made our first landfall in late afternoon of the second day and spent the next four days cruising though the South Shetland Islands and along the Antarctic peninsula making a total of ten Zodiac shore excursions to as many different and wonderful destinations. (A Zodiac is a rubber boat with an outboard motor holding about a dozen people that we used to get from the ship to the shore). The Zodiac rides themselves were often as much fun as the landings and involved some tricky disembarkations from our rolling ship’s ladder and some wet landing on the beach in our big rubber boots. Each excursion was different and exciting. Among the highlights were:

Bailey Head, Deception Island. Eager with anticipation for our first landing, we came ashore on a rocky beach, which was the home to a colony of chin-strap penguins . . . not 200, not 2,000 but 200,000 on the beach, up the nearby hills and into the adjacent valleys as far as the eye could see. The sight (and smell) of so many of these unique, little birds was overwhelming and unforgettable.

It’s hard not to fall in love with penguins. We saw seven different varieties on our cruise. The chin-strap, as the name implies, has a black strap line under its chin and looks like a wind-up, drummer boy. With no history of predation, the birds are absolutely unafraid of humans and very willing to approach you within a foot or two . . for conversation or a simple look-see. This was the first chapter in the love affair which we all developed with these little bird-people over the course of the cruise.

Chinstrap Penguin Macaroni Penguin Adele Penguin |

Neko Harbor. Unable to make a landing because of the sea and ice conditions, we spent a couple hours in our Zodiacs cruising around the bay among the icebergs. Although we’d seen them at a distance the previous day, their size, shapes and colors (blue, green and snow-white) are awesome at this close range, a floating gallery of fantastic sculptures.

It was in these waters that we had our first close encounters with the giant humpback whales that came close alongside the ship and escorted us through the ice filled channel. Although we were to see other varieties of whales along the way . . . minke, fin and orca (killer) whales along with hour-glass dolphins, these forty ton leviathans are an awesome presence. It is thrilling to know that we share the planet with these great mammals and particularly so, when you think that they had been down there patrolling the oceans for over 200 million years before man arrived on the earth..

Cuverville Island. A chance to hike to the top of a long, snow covered slope for a panoramic view of the channel beyond . . . and to slide back down the slope on our . . . . waterproof pants made this a fun excursion. We were joined in the slide by a colony of gentoo penguins . . . the most ubiquitous variety on the peninsula, the "gentle gentoos" with the white triangle over their eyes.

Petermann Island. This was the southernmost stop on our voyage . . 65° 20’ South Latitude. . about 75 miles north of the Antarctic Circle. Having crossed the Arctic circle in our Alaska trip thirteen years ago, it would have been fun to cross the Antarctic Circle as well . . but the pack ice was beginning to form again as the Antarctic summer came to an end and it would not have been possible. In fact, another cruise ship had become temporarily stuck in the ice down there a week before which tended to reinforce the decision. (It’s worth noting that in our seventeen days in the Antarctic waters, we did not see another cruise ship anywhere. There were a few other ships in the region but they are in radio contact with each other and work hard to maintain a distance in order to preserve the sense of isolation which is an important part of the Antarctic experience).

At Petermann, we had our first and only exposure to the comical Adele penguins which generally prefer the even more southern latitudes.

Pendulum Point, Deception Island. With some agile seamanship, the ship made its way into the volcanic crater (caldera) at Deception Island though a narrow break in the crater wall. There we had the unique opportunity to take a swim in the Antarctic ocean, along a beach where the waters are heated by the steam from the active volcano below. Not the greatest bathing experience ever, your feet were hot and your head was freezing . . . but, as they say, on average it wasn’t bad. We must have presented a strange sight to the onlooking penguins.

Elephant Island. Our last stop before leaving Antarctica was at Elephant Island, where Shackleton’s men waited for four months on a narrow, exposed beach for their leader to return and rescue them.. For those that might not know the Shackleton story, it is worth a quick retelling. ( In fact, the story of his adventure is the subject of a truly great book by Alfred Lansing called "Endurance" and well worth reading") This story as much as anything else was one of the motivators of our visit to Antarctica and gave us the chance to follow in the footsteps of this amazing explorer.

Ernest Shackleton and his 27 man crew set out for Antarctica with the hopes of making the first overland crossing of the continent. Caught is an early freeze, his ship the "Endurance" was captured in the pack ice and eventually crushed. The men abandoned the ship and camped on ice floes for five months before winter ended and the ice began to break up forcing them to row their small boats to Elephant Island, their first contact with land in twenty months. Realizing that rescue was impossible, in an amazing feat of seamanship and navigation, Shackleton took five men and sailed a 22 foot open boat some 800 miles across the dreaded Drake passage, where after seventeen exhausting days they reached South Georgia Island.

Unfortunately, some formidable mountain peaks still separated them from the whaling station on the other side of the island but somehow, half-dead they managed to climb the heretofore unscaled mountains and arrive to the whaling station and safety. From there, Shackleton was able to find a ship to return with him to Elephant Island to rescue his men who had been living on penguin meat and prayers for 120 days. The men never doubted that he would return and not one of the men in his expedition lost his life thanks to Shackleton’s extraordinary courage and leadership.

With it’s black crags jutting into a low-hanging sky, Elephant Island is a foreboding place and as we circled the Point Wild in our Zodiacs, we found it is impossible to imagine what those men must have endured over the four month period that they waited on this tiny, exposed beach for Shackleton. Following the course of his 800 mile sea voyage over the next two days, we found it even more impossible to imagine what that crossing must have been like in his open boat.

Scotia Sea.

Our two day crossing voyage through the Scotia Sea to South Georgia Island was again blessed with friendly seas which probably took a bit of the edge off a true appreciation of the hardships that Shackleton must have faced along the same route eighty-four years earlier.

For us cruise ship sailors, it was a great opportunity to stand out on the afterdeck and watch the giant albatross soaring along beside the ship. Although they were often joined in their graceful ballet by other southern sea birds . . petrels, skuas, prions, turns and gulls, there is something majestic about the flight of the wandering albatross that, with an absolute economy of motion of his eleven foot wingspan, is able to roam the southern oceans for up to five years at a time without ever returning to land . . .circling the globe ten or more times in their lifetimes.

The crossing also introduced us to increasingly larger and more numerous tabular icebergs, which are flat topped, steep sided icebergs that had calved off the Weddell ice shelf. Many were over 200 feet high and a mile or more in length. One record berg broke off from the Ross Ice Shelf just after we were there that measured 183 miles by 22 miles (twice the size of the state of Delaware). Although the presence of these monster bergs in our waters may have resulted in a few suppressed thoughts about the "Titanic" . . . fortunately these giant icebergs are all now tracked by satellite as well as by the ship’s own radar. Our captain encouraged an "open bridge" policy, which allowed passengers to spend time on the bridge any time day or night . . . a real treat for an old aircraft carrier sailor like me.

South Georgia Island

South Georgia Island, appearing on the map as a tiny speck in the far South Atlantic Ocean, is located in one of the most desolate parts of the earth a thousand miles east of Cape Horn. It is characterized by high mountains capped by eternal snows, which tower 9,000 feet above the sea. During the polar summer, it offers Antarctic wildlife a place to mate and raise their young. The planet’s greatest concentration of seals, penguins and albatross crowd its shores. It is truly the Garden of Eden of the Antarctic region . . . an icy paradise.

As on the Antarctic peninsula, the wind and sea conditions dictated our itinerary and we were prevented from making several scheduled landings due to in one case to high winds, in another to a threatening iceberg and even to a crowd of unfriendly seals blocking our landing site in a third. Nevertheless, we did make a series of unforgettable visits to South Georgia:

Cooper Bay. Our first landing on South Georgia Island was at Cooper Bay to visit a colony of macaroni penguins . . . notable for their long, yellow, swept-back eyebrows. They are the Yankee Doodle dandies of the penguin world. Although there are five million macaronis on the island, they nest in generally inaccessible places so we were fortunate to have a chance to see and photograph these most distinctive of penguins.

The beach at Cooper Bay was shared with hundreds of seals . . . both fur and elephant seals. Hunted close to total extinction in the 18th and 19th centuries, they have both made remarkable comebacks . . . with over two million fur seals and a half million elephant seals at South Georgia alone. We watched the baby seals yelping and rollicking in the surf while the adults kept a check on their proceedings with an occasion growl or nip. It is amazing how agile these seals are with only their articulated flippers to propel them along. The elephant seals . . . some weighing up to 4,000 pounds . . . simply snored, snorted and grunted their morning away while lying in huge herds at their end of the beach.

Gold Harbor. Probably our favorite landing site of the entire cruise, Gold Harbor is a glorious stretch of dark sand in a gently arcing bay surrounded by snow covered mountains . . . and home to a colony of thousands of king penguins. With their glowing yellow bibs and orange ear patches, these three-foot tall creatures are the most striking of all the members of the penguin family. We followed them down the beach to a rookery a mile or so away. There, thousands of penguins stood on their appointed spots in this penguin nursery incubating their single egg (which they set on their feet and hold in place by a fold of skin) or nurturing their chicks. The male and female, who mate for life, alternate with each other in baby sitting and going to sea in search of food for their young.

Mom and Dad King Penguin

....expecting

... their new arrival Mom and Dad King Penguin

....expecting

... their new arrival |

As ungainly as penguins appear on land, it is hard to reconcile their waddling walk with the sleek, torpedo-like figures that we saw porpoising alongside our ship every day at speeds up to seven miles an hour (sometimes as much as two hundred miles from land) in search of food. Sometimes I wonder if they don’t just affect their comic, Chaplin-esque walk for the amusement of tourists and then fly away after all the tourists have left.

Grytviken. Grytviken Harbor is the location of the oldest of some half dozen whaling stations on South Georgia Island. It operated from 1904 until 1965 when the whaling population of the southern waters were exhausted. The whaling station at Grytviken is now a ghost town with its abandoned hoists, chains, giant oil tanks and even a grounded whaling boat create a silent reminder of the three hundred men who once worked here and the more than 250,000 whales that were slaughtered here. Few people would now support whaling as it was carried out throughout the sixty years of Grytviken’s history but attitudes were very different a generation ago and it was a highly respected profession for the whalers of that day. Although it is, in retrospect, an example of human folly, it is also an example of a remarkable human endeavor that built this once important industry in a desolate corner of the world, many thousands of miles from home.

Grytviken is also the home to the only inhabitants of this island . . a British couple, Tim and Pauline Carr, who have been living here on their small boat for the past seven years, the harbormaster and his wife and small, lonely garrison of British soldiers, who have been stationed here since the Falkland Island war. (The first shots of that war were fired here). And finally, Grytviken is the final resting place for Sir Ernest Shackleton, who died here at age 48 of a heart attack five years after his storied return from Antarctica. As is custom, we all took a small glass of rum and drank a toast to "the boss", as he was known, at his graveside.

Prion Island. A long hike to the top of a grassy tussock covered hill brought us to the nesting place for a large colony of wandering albatross . . . one of the few places on the island that offers them enough "runway" space for them to take flight . . . a vital consideration for a twenty-five pound bird with an eleven foot wingspan. When a newly fledged albatross flies for the first time, it will generally not return to dry land for another five years. We had seen a similar nesting ground for the royal albatross two years ago in New Zealand and we were privileged here to witness several pairs performing their courtship dance ("gaming") with wings outstretched and necks bobbing and weaving together.

Falkland Islands

Like many people, I suspect, we didn’t know much about the Falkland Islands before the Argentineans invaded it in 1982 in their unsuccessful attempt to wrest control of the islands from Great Britain. And so, it seemed strange to find ourselves actually in the Falklands following a two day passage from South Georgia. The Falkland Islands are a collection of two hundred, wind-swept islands located three hundred miles from Argentina (and seven thousand miles from England) . . . with two thousand British citizens living in the capital at Port Stanley or on the sheep farms spread across the islands.

Although we hiked out to a colony of magellanic penguins and made a Zodiac visit to a collection of rock hopper penguins (Does this make seven varieties?) , it was the aftermath of the recent, bloody war that absorbed much of our attention. As a result of a horrific miscalculation on the part of the Argentine military government, over a thousand young men . . . 250 British, 750 Argentine . . . lost their lives in this brief and distant war. Not just the war but the two hundred thousand unexploded land mines left behind by the Argentine military, have left the islanders with a constant reminder of this terrible war along with a bitter aftertaste that will take a long, long time to overcome. If one ever needed a reminder about the devastating effects of land mines and the tragedy of war, the Falkland Islands provides an all too vivid and recent lesson.

From the Falkland Islands, we flew back to Santiago for a one day layover and then on home to the United States. Although we have always resisted answering the question of what was our greatest trip ever, it will be difficult to resist such a ranking with this trip to the Bottom of the World. It was a once-in-a-lifetime adventure that certainly far exceeded all of our hopes and expectations. Maybe the best answer is simply that the best trip was the last one we just took or, better yet, the next one to be taken